Participatory mapping in Bili-Uere recovers wildlife in the Congo Basin

African Wildlife Foundation worked with DRC's Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature to engage communities in land-use planning

The Congo Basin features the world’s second-largest rainforest and is home to endemic and biologically diverse flora and fauna. Amidst this immense natural wealth are millions of people who are integral to these biodiverse ecosystems and depend on the natural resources they contain. However, commercial and illegal logging, industrial and artisanal mining, the illegal bushmeat trade, poor agricultural practices, and armed conflict threaten natural ecosystems and closely related livelihoods.

These threats do not spare the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex, an expansive landscape in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) has collaborated with the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN). In 2018, AWF launched the Community Based Counter Wildlife Trafficking (CBCWT) project with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to contribute to the conservation of this ecosystem by proposing alternative and sustainable solutions to the anthropogenic activities that degrade the landscape.

“Within the framework of this project, AWF proposed to carry out participatory mapping, knowing that it is unthinkable, if not impossible, to control the activities of the local community without setting up a land-use plan, the aim of which is to allocate each portion of land to a very specific use,” explains Antoine Tabu, AWF Country Coordinator and Deputy Chief of Party for the CBCWT/USAID project.

For the project's duration, AWF worked with two chiefdoms located in the central zone of the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex, including five groups from Goa and four from Gwamangi.

“Everything starts with awareness-raising [and discussions] with all stakeholders gathered in focus groups, for instance, fishermen, farmers, and hunters, to find out about their use of natural resources and understand their real needs for personal and community development. The idea is to obtain Free Informal Consent FPIC) in advance (so that the rate of appropriation of the results is high,” explains Jean-Claude Kalemba, a former AWF GIS Assistant, whose bravery has been invaluable throughout the implementation of the CBCWT/USAID project.

“The truth is, when AWF [contacted] me, I had a lot of grey areas, and my community even thought I was plotting with them to change the group’s boundaries. However, through the various awareness-raising sessions, the slightest abstract concepts were explained. As a result, I was able to see the enthusiasm that animated us all when we took part in the participatory mapping activities,” testified Gbandali Hala Hulu Marcel, Gwamangi group leader. “You have to admit that this mapping was indeed participatory,” he adds, shaking his head in approval.

After the meetings, the team interviewed community leaders (group and chiefdom heads) to identify a quota of community members with a basic knowledge of geography to form a team of community guides. In total, 1344 people were involved in this process, including 1,120 people who were sensitized and 224 community guides.

“Once identified, community guides are trained in GPS use and data collection. For three days, they receive theoretical instruction, after which we accompany them into the forest for one or two days of practical sessions,” continued Kalemba.

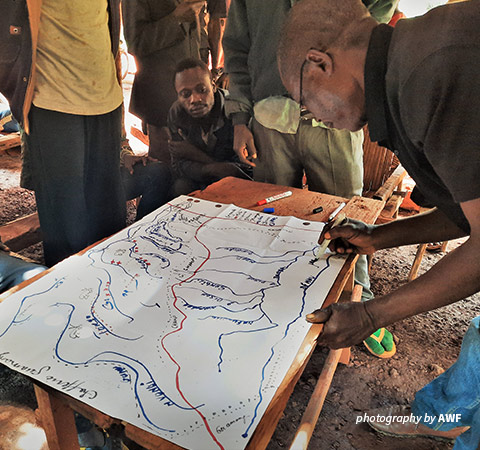

Community representatives participated in freehand mapping

Boundaries set the foundation of natural resource management

After these stages, the participatory mapping process consists of bringing together the local community and their leaders to draw freehand the boundaries of each grouping on the ground before proceeding on paper. During this process, participants also identify the sites that will be the subject of data collection.

“After this process, we sent out community guides, divided by site, to collect the data. On their return, we analyzed and processed the data obtained and produced the first maps illustrating the boundaries of the various clusters and the distribution of activities within them,” explained Phila Kasa, AWF Community Development Manager.

Kasa explained that data collection was the most challenging stage, as most clusters had lost their natural boundaries. “But during the presentation of these results, the heated debates brought out the light through recommendations that enabled us to produce new maps unanimously approved,” he pointed out.

After that, AWF presented maps demarcating the areas of permanent and non-permanent forests to illustrate the level of damage caused to the habitat and to propose to the local community the support that AWF will provide in return for the adoption of certain pro-conservation practices.

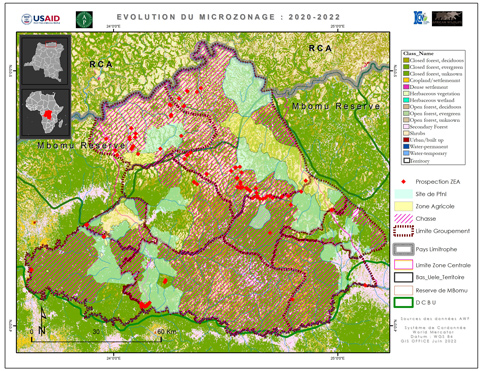

“During the five years of the Community Based Counter Wildlife Trafficking project, we completed the participatory mapping of nine groups in the central Bili-Uere zone and organized validation workshops to define a land-use plan in which 4,527 sq. kilometers of the 11,000-sq.kilometer central zone was designated as ecological corridors, while the other parts were defined as agricultural zones, hunting zones, zones for collecting non-timber forest products, fishing zones, and artisanal mining zones,” underlines Tabu.

Nine groups mapped in the central zone of the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex

“The question of boundaries has always been very complex and is the Achilles heel of local communities. It is, therefore, thanks to the flexibility, understanding, patience, and friendliness with which the AWF and ICCN teams worked throughout this process that we have achieved these joint results,” attests Bernard Iyomi, Site Manager of the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex.

The participatory mapping results have been the compass guiding all community development activities implemented in this landscape. “Recreating these areas of land and offering shelter to light-faced chimpanzees, forest elephants, and all the other species that use it as an ecological niche is a way of guaranteeing the origins and roots of the Zandé people,” as Jean-Claude Kalemba used to say repeatedly during all his meetings with the local community of the Bili-Uere landscape.

Thanks to this participatory mapping process, we could map 12,824.88 sq. kilometers of the forest block, 1,122.86 sq. kilometers of land dedicated to agriculture, 2,255.41 sq. kilometers to gathering, and 9,131.88 sq. kilometers to hunting. In the agricultural areas, AWF has organized training courses on sustainable farming techniques and provided improved seeds to increase farmers’ production. Overall, the CBCWT project has enabled households to increase their incomes and diversify their sources of livelihood, gradually lifting them out of poverty while ensuring a sustainable future for the Congo Basin’s natural resources.

> Learn how AWF introduced sustainable farming to improve livelihoods in Bili-Uere