Kenya’s 2025 Conservation Journey: How Today’s Foundations Are Shaping Tomorrow

Group Photo of the AWF Young Conservation Champions Scholarship winners and AWF staff during the conservation education launch.

At the height of the driest months in northern Kenya, you can read a landscape by its sources of water. A watering hole that holds a little longer draws herders, wildlife, and daily life into the same narrow radius. When rivers and springs shrink, that radius tightens—and the chance of conflict rises just as livelihoods become more fragile.

This was the backdrop to AWF Kenya’s work in 2025. In a year marked by major events across conservation in Kenya and globally, our team stayed focused on practical solutions that reduce pressure on people and on ecosystems: reliable water access, livelihoods that restore rather than degrade, youth engagement that is meaningful, and governance systems that keep conservation benefits inclusive and transparent.

Across Marsabit County, priority wildlife corridors, and community conservancies—including the Tsavo landscape—we worked with county governments, community groups, youth leadership structures and community-based organizations to strengthen Kenya’s conservation influence by keeping people, wildlife, and landscapes at the center.

Marsabit County: Livelihoods That Restore Land and Strengthen Resilience

AWF Kenya Country Director Nancy Githaiga (far right) enjoying song and dance with community members.

In 2025, AWF partnered with BOMA with the support of the Light Foundation and local groups to deliver the Sustainable Opportunities for Improved Livelihoods (SOIL) project—an “Entrepreneurship for food security, nutrition, and child wellbeing” initiative targeting Marsabit County, one of Kenya’s historically marginalized regions.

In less than a year, SOIL began delivering measurable, on-the-ground change. 13 community engagement sessions reached more than 1,000 participants with guidance on climate resilience and natural resource management. 190 households were selected to receive improved cookstoves and solar energy systems, easing pressure on forest resources. Four community tree nurseries were established in Arapal, Merille, and Hurri Hills to support reforestation and fruit tree planting.

The project also supported community groups to adopt sustainable rangeland and water management practices—including desilting and structured water access at key watering holes such as Arapal and Hurri Hills—so scarce water points can serve people and livestock more predictably while allowing degraded areas to recover.

In schools, environmental clubs in all 10 participating institutions launched practical initiatives in poultry farming, tree growing, and kitchen gardens—connecting conservation to nutrition and livelihoods in ways that are tangible to students and their families.

Water Security: Infrastructure That Supports People, Livestock, and Wildlife

Livestock at a watering hole in Tsavo East National Park.

Water scarcity remains one of the most persistent drivers of human-wildlife conflict and livelihood instability across Kenya’s priority landscapes. AWF Kenya’s approach in 2025 prioritized water infrastructure that serves people, livestock, and wildlife simultaneously paired with landscape-wide planning that can hold up under increasing climate stress.

In 2025, these interventions enabled more than 6,500 households to access improved water supplies, supported more reliable access for more than 2,500 livestock, and improved water availability for over 1,000 elephants across priority landscapes.

The ripple effects are significant. Better water access improves sanitation and supports school attendance in impacted communities. It also reduces pressure on rivers and springs, creating space for riparian regeneration and habitat restoration, which is essential for long-term water security.

Youth Engagement: Building Conservation Leadership That Lasts

The Recipients of the 2025 AWF Young Conservation Heroes Scholarship from the left to right: Robert Kilapai, Zipporah Mumo Kiminza, Abdulrahym Godhana Garise, Swabrina Esmael, Mwamtutu Hamisi Mwaiwe.

Conservation outcomes are not sustainable if they end with a project cycle. They hold when young people can see conservation as a pathway into leadership, into policy, and into the everyday choices that shape land and water use.

In 2025, AWF expanded youth engagement through the Young Conservation Heroes initiative, in partnership with Wildlife Clubs of Kenya (WCK). Two model schools were established within the Tsavo landscape to serve as hubs for landscape-wide conservation education events, engaging more than 500 learners drawn from 130 schools. And with conservation education and information materials developed, the engagement reverberates beyond the landscape to schools across the country, where our partner, WCK, has a presence.

In Marsabit County, the SOIL project reinforced this momentum through the establishment of wildlife clubs in 10 schools, demonstrating a simple lesson: Youth engagement scales best when it grows alongside practical landscape investments, such as water access, restoration, and sustainable livelihoods.

Policy and Governance: Keeping Kenya’s Conservation Gains Credible and Inclusive

In 2025, Kenya’s policy environment also shifted in ways that will shape conservation outcomes for years to come. AWF Kenya stayed engaged in these conversations, because enabling policy is not an abstract exercise—it is what determines whether conservation benefits are shared fairly and whether decision-making is grounded in evidence.

The proposed Wildlife Conservation and Management Bill, drafted to address perceived gaps in the 2013 law, opened important debate on benefit-sharing for Indigenous communities, stronger inclusivity in leadership selection for boards, such as the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), and the severity of penalties and fines. Through rolling public participation sessions, AWF supported the intention to strengthen governance while raising three core concerns.

First, the shift toward a more bioeconomy framing could normalize extractive activities, such as mining within conservation areas through permitting. Second, proposals to establish overlapping new bodies—like the Kenya Wildlife Regulatory Authority, Kenya Wildlife Research and Training Institute, and a National Wildlife Tribunal—risk the duplication of mandates, unclear appeal pathways, and friction across services. Third, proposals that would place conservation and wildlife data behind paywalls for Kenyan citizens raise legitimate questions around freedom of access to information and copyright.

The year also saw the release of the 2024–2025 National Wildlife Census, consolidating data spanning six decades (1958–2025) to better inform national decision-making. The rebound of major species, such as elephants and rhinos, offers hope. At the same time, rising poaching cases for species such as pangolins underscore why monitoring, enforcement, and community engagement must remain central. The Census’s recommendations—formalizing conservation as a land use, prioritizing wildlife corridors and threatened species and ecosystems, strengthening national databases and monitoring systems, and restoring increasingly fragmented habitats—align closely with ongoing AWF Kenya programming, including land restoration, water infrastructure, community engagement, and data aggregation.

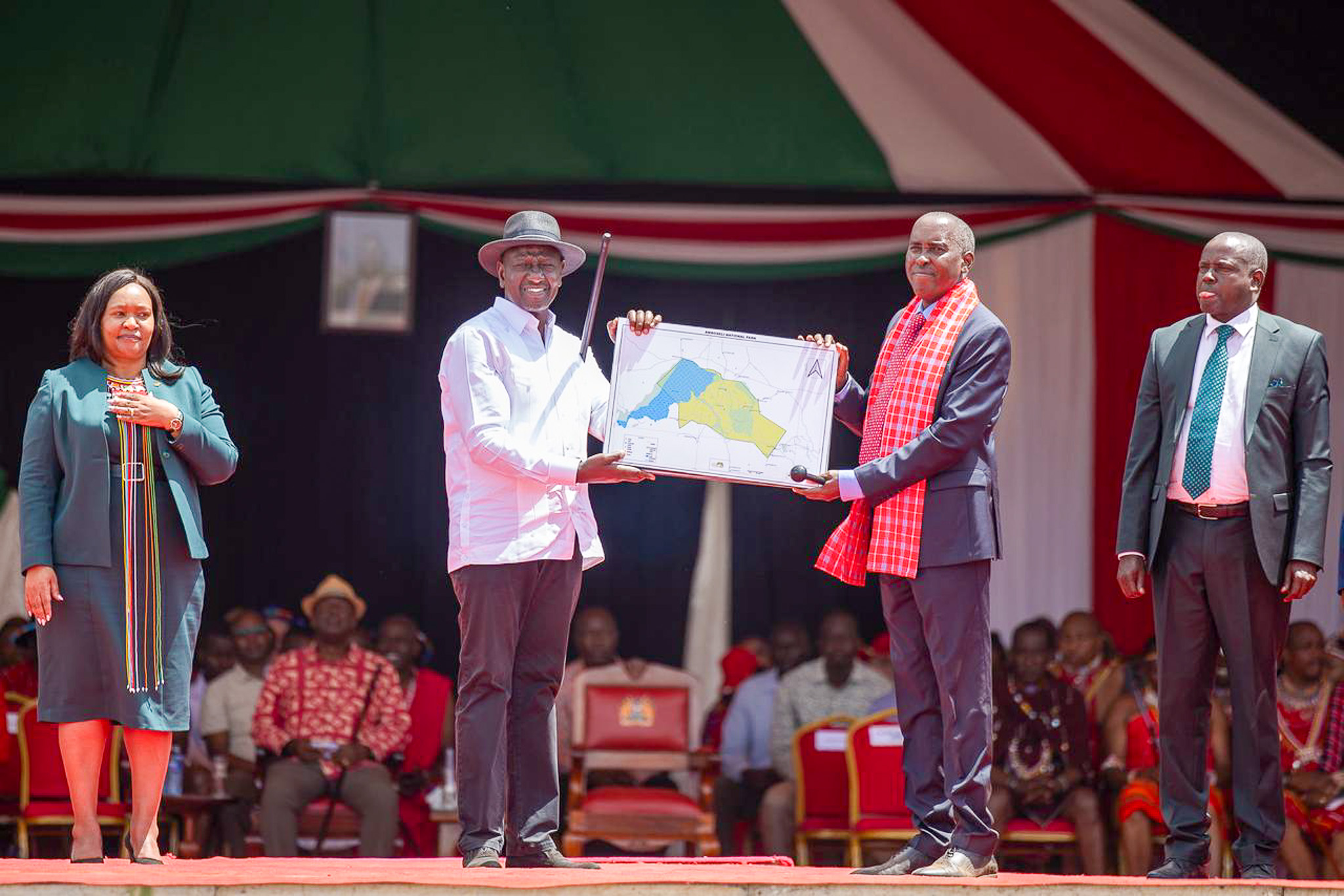

H.E. Dr. William Ruto, President of the Republic of Kenya, and H.E. Joseph Ole Lenku, Governor of Kajiado County, during the handing over of the Amboseli National Park.

A further milestone was the historic handover of Amboseli National Park from the national government to Kajiado County—an encouraging step toward local stewardship and community-led conservation. AWF remains a strong supporter of the County Government of Kajiado and the communities in the Amboseli ecosystem, in their quest for a sustainable and equitable way of managing this critical ecosystem through the development of an integrated masterplan.

Looking Ahead to 2026: Protect the Gains, Plan for the Growth

Kenya’s conservation challenges can look daunting in aggregate, but the pathway to progress is practical: Identify pressure points, address them systematically, and invest in what reduces risk.

Wildlife corridors and easements are a priority. When these routes are protected and publicized, species retain access to historic movement pathways and the genetic exchange that underpins healthy populations—while human activities are guided away from high-risk interfaces, protecting both people and wildlife. Responsible water resource management is equally central: When scarcity is reduced, conflict drops and ecosystems have room to recover.

In 2026, AWF Kenya will continue strengthening the core pillars of water, livelihoods, youth, and policy—while deepening our engagement with development pathways that will shape ecosystems for decades. This will be especially visible in our work on the LAPSSET Corridor initiative (Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport Corridor), a suite of infrastructure megaprojects—including highways, railroads, airports, and special economic zones—stretching from South Sudan to the Kenyan coast as part of the Greater African Equatorial Land Bridge Project.

Projects of this scale can either entrench fragmentation or catalyze a just transition. AWF is a partner to the consortium advancing LAPSSET, and we will provide technical input and recommendations to help ensure that environmental safeguards, community outcomes, and landscape connectivity are built into decisions from the outset.

The foundations of 2025 are not an endpoint. They are a platform. With strong partnerships and sustained investment, Kenya can continue to show what people-centered conservation looks like—where water flows, landscapes recover, communities benefit, and wildlife thrives.